The Manitoba government will establish a new $10-million loan fund to support social enterprise, creating more employment and training opportunities for people who face barriers to work, Housing and Community Development Minister Mohinder Saran announced last week at the sod-turning of a new 19-unit multi-family housing project that will be built, in part, through social enterprise.

The Manitoba government will establish a new $10-million loan fund to support social enterprise, creating more employment and training opportunities for people who face barriers to work, Housing and Community Development Minister Mohinder Saran announced last week at the sod-turning of a new 19-unit multi-family housing project that will be built, in part, through social enterprise.

“Manitoba is proud to invest in unique solutions to address difficult challenges like poverty, unemployment and social exclusion,” said Minister Saran. “This new loan fund will provide social enterprises with the financing tools needed to succeed. As a result, more Manitobans will have the opportunity to learn new skills, access social supports, participate in training and find meaningful employment.”

The new $10-million social enterprise loan fund will help employment-focused social enterprises access capital with flexible loan financing including start-up, operating or emergency loans and loan guarantees. Social enterprises are non-profit organizations that use a business model to achieve broader social goals, an approach the minister noted can effectively provide a path out of poverty for people who face barriers to employment.

The loan fund builds on the recommendations of the 2015 Manitoba Social Enterprise Strategy and will be developed in partnership with the social enterprise sector, the minister noted.

“Access to the right money at the right time, as well as exploring and developing markets, including public procurement, are important pieces of the Manitoba Social Enterprise Strategy,” said Sarah Leeson-Klym, regional director, Canadian Community Economic Development Network. “As the community hosts of this strategy, we’re pleased the province is finding ways to support the impact of training and employment-focused social enterprises while also moving forward on their commitments to create affordable housing.”

The minister highlighted this new commitment at the sod-turning of Austin Family Commons, a new affordable housing project that will replace three vacant lots at 150 Austin St. North.

“The Austin Family Commons project will make a real difference for families in the North Point Douglas neighbourhood,” said Minister Saran. “We are excited to partner with community agencies, our builders and social enterprise to ensure the construction of these new units will create job opportunities for people who have experienced employment barriers. This is a win-win for the entire community.”

Once complete, Austin Family Commons will be a three-story, 19-unit family apartment building. Rents will be set at affordable levels and half the units will offer rents geared to income. The minister noted the site provides easy access to a range of local amenities and major public transportation routes on Main Street, making it ideal for local workers and future tenants.

“Nothing takes a bigger bite out of poverty and all its symptoms than a job,” said Lucas Stewart, general manager, Manitoba Green Retrofit (MGR). “Social enterprises like MGR use entrepreneurial tools to create meaningful and, most importantly, sustainable jobs for Manitobans who might otherwise be unemployed. Financing from this loan fund will provide social enterprises with tools to play a much bigger role in many future projects like this one. This is good policy and smart spending.”

Minister Saran noted this project supports Manitoba’s commitment to developing new affordable rental housing for families. Construction is expected to be completed in early 2017, he added.

The minister also announced the Manitoba government will develop a government-wide social impact procurement policy to broaden public-sector support for social enterprise and help ensure that existing purchasing leads to more job opportunities for people otherwise excluded from the labour market.

For more information about the Manitoba Social Enterprise Strategy and affordable housing in Manitoba, visit www.gov.mb.ca/housing.

SOURCE: Province of Manitoba

Congratulations to

Congratulations to  The Canadian Alternative Investment

The Canadian Alternative Investment The federal government has released an open invitation for pre-budget submissions from Canadians in advance of the 2016 Federal Budget. The government has not set a date for the finalized budget but it will likely be published before the end of the fiscal year (March 31).

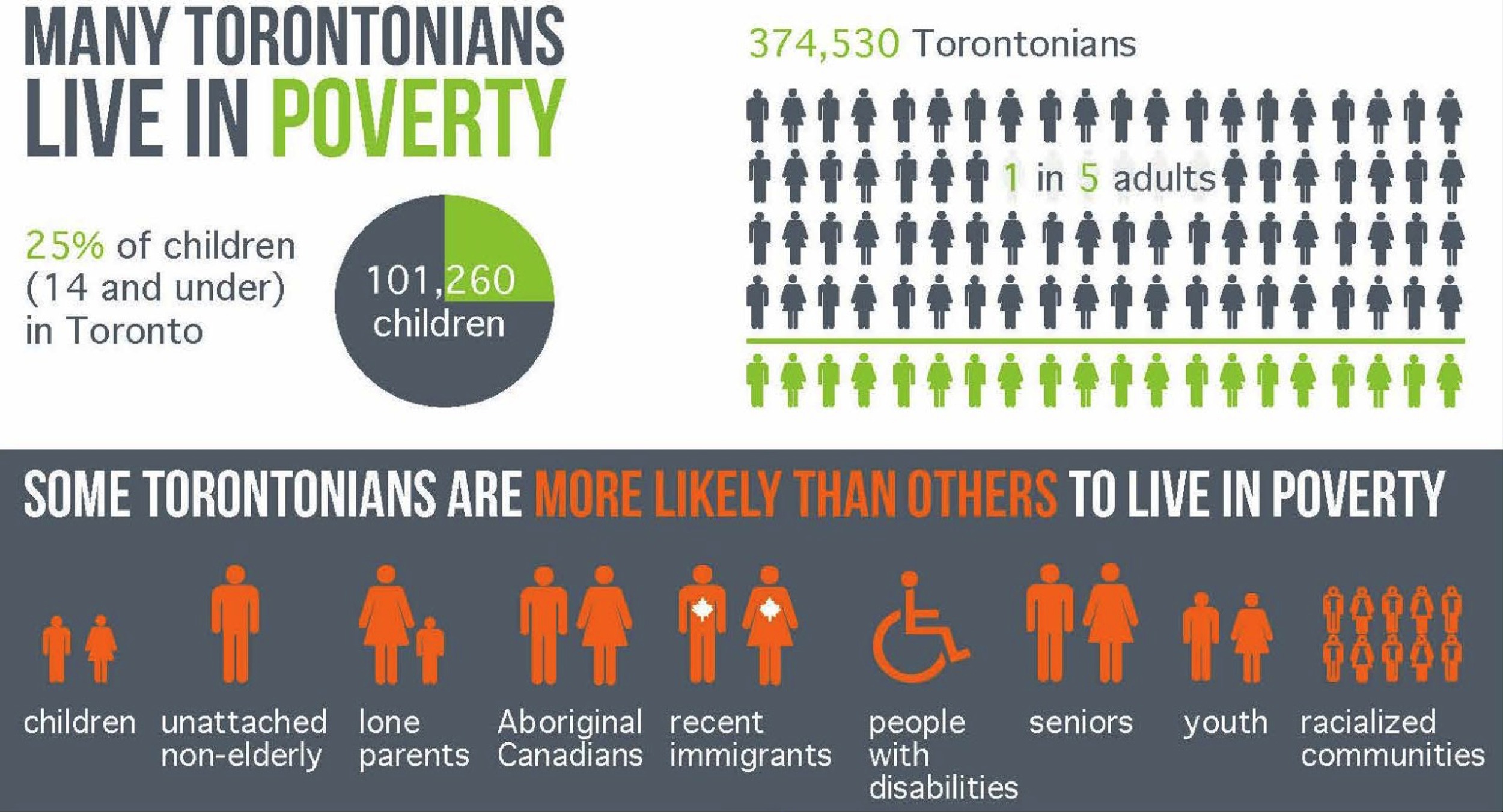

The federal government has released an open invitation for pre-budget submissions from Canadians in advance of the 2016 Federal Budget. The government has not set a date for the finalized budget but it will likely be published before the end of the fiscal year (March 31). Like many major metropolitan areas in the United States, Toronto is experiencing fast-paced growth. Canada’s finance and business capital has more cranes in the sky than New York City—with nearly 50 percent more high-rises undergoing construction than in the big apple. Between 1990 and 2012, the region experienced a doubling of the economy, and significant population growth. By 2013, Toronto had become the fourth largest city in North America and today, almost one fifth of all Canadians live in the metropolitan area.

Like many major metropolitan areas in the United States, Toronto is experiencing fast-paced growth. Canada’s finance and business capital has more cranes in the sky than New York City—with nearly 50 percent more high-rises undergoing construction than in the big apple. Between 1990 and 2012, the region experienced a doubling of the economy, and significant population growth. By 2013, Toronto had become the fourth largest city in North America and today, almost one fifth of all Canadians live in the metropolitan area.  Amidst such frenzied development and economic growth, however, many have been resigned to the margins:

Amidst such frenzied development and economic growth, however, many have been resigned to the margins:

Michelle Stearn began working at the Democracy Collaborative as a Communications Associate in Fall 2015 after graduating from Georgetown University with a Bachelor’s degree at the School of Foreign Service. Her studies focussed on environmental justice, globalization, and critical theory. She also studied sustainable community development and urban agronomy for a semester in Santiago, Chile, where her Spanish accent became quite distinctive.

Michelle Stearn began working at the Democracy Collaborative as a Communications Associate in Fall 2015 after graduating from Georgetown University with a Bachelor’s degree at the School of Foreign Service. Her studies focussed on environmental justice, globalization, and critical theory. She also studied sustainable community development and urban agronomy for a semester in Santiago, Chile, where her Spanish accent became quite distinctive. Violeta Duncan began working for the Democracy Collaborative as an Associate, Community Wealth Building Research & Strategy in May of 2014. She received her undergraduate degree from Washington University in St. Louis and her master’s degree in urban planning from Columbia University, where she concentrated on participatory planning and local procurement practices in Kenya. Duncan assists in the production of the monthly Community-Wealth.org newsletter and maintains the Community-Wealth.org blog, in addition to supporting feasibility studies and other community wealth building research.

Violeta Duncan began working for the Democracy Collaborative as an Associate, Community Wealth Building Research & Strategy in May of 2014. She received her undergraduate degree from Washington University in St. Louis and her master’s degree in urban planning from Columbia University, where she concentrated on participatory planning and local procurement practices in Kenya. Duncan assists in the production of the monthly Community-Wealth.org newsletter and maintains the Community-Wealth.org blog, in addition to supporting feasibility studies and other community wealth building research.

In his recent

In his recent  In 2016, LITE will award Community Economic Development Grants in the month of June. Grant recipients will be notified in May.

In 2016, LITE will award Community Economic Development Grants in the month of June. Grant recipients will be notified in May.

Cities offer the scale needed for transformative change — large enough to matter, but small enough to manage. Universities and colleges are also civic actors in their own right. They are “cities within cities,” where the principles of pluralism create communities of diversity, open to the world. The relationship between post-secondary institutions and cities can serve as an engine of social and environmental sustainability. As part of its pursuit of a more inclusive, sustainable, and resilient society, the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation has created RECODE, an initiative dedicated to catalyzing social innovation and entrepreneurship in higher education; and Cities for People, which contributes to more resilient, livable and inclusive cities.

Cities offer the scale needed for transformative change — large enough to matter, but small enough to manage. Universities and colleges are also civic actors in their own right. They are “cities within cities,” where the principles of pluralism create communities of diversity, open to the world. The relationship between post-secondary institutions and cities can serve as an engine of social and environmental sustainability. As part of its pursuit of a more inclusive, sustainable, and resilient society, the J.W. McConnell Family Foundation has created RECODE, an initiative dedicated to catalyzing social innovation and entrepreneurship in higher education; and Cities for People, which contributes to more resilient, livable and inclusive cities. Poverty reduction has no silver bullet. Nor should we expect one. The exhausting and overwhelming work of reducing poverty must take a comprehensive, long-term approach that is led by the communities in need. These communities, who struggle against poverty and social exclusion every day, have repeatedly said this work requires more than a simple transfer of money.

Poverty reduction has no silver bullet. Nor should we expect one. The exhausting and overwhelming work of reducing poverty must take a comprehensive, long-term approach that is led by the communities in need. These communities, who struggle against poverty and social exclusion every day, have repeatedly said this work requires more than a simple transfer of money. Blog by: Darcy Penner

Blog by: Darcy Penner